Wojciech Kozłowski, Zielona Góra 1979-1991. The Unrecorded Myth

Wojciech Kozłowski

Zielona Góra 1979-1991. The Unrecorded Myth

Zielona Góra entered the 1980’s as a city which was still working on building its cultural identity. It was a testing ground for the cultural strategy of the state which, as Andrzej Turowski writes: “from the mid 1950’s onward was based on limiting, stimulating or intercepting means of imaging into the orbit of its own ideology”[1].

The local melting pot of people who had come here after the war, streaming in from different parts of Poland, founded two colleges, opened a number of cultural institutions, and started a biweekly dedicated to arts and culture, hosting an array of writers, not necessarily from Zielona Góra. It would be stretching it to say that there was a bubbling cultural life in the town, however there were people who were able to carry out their plans regardless of the limitations imposed by the omnipotent state.

Every two years, beginning in 1963, the city played host to a national event - The Exhibition and Symposium of the “Golden Bunch” [Wystawa i sympozjum “Złotego Grona”]. Marian Szpakowski, the author of the idea and its organizer, was extremely skilled in taking advantage of the authorities’ weakness to seek self-legitimacy via culture. Obviously, such realization of one’s plans was conditioned by the extent to which these plans were in line with the objectives of those in power. As Konrad Schiller writes in an unpublished master’s thesis on the “Golden Bunch”: “[…] it was the artists who were responsible for the form of the event, though the objectives were determined by the local authorities”[2]. Schiller quotes Jan Koleńczuk, deputy head of the Presidium of the Voivodship National Council, who said: “the event provides us with a multitude of possibilities to get acquainted with the achievements of the most important artistic milieus in the country. […] The fact that this significant cultural occasion is taking place in the Western Territories of Poland proves that they have been entirely integrated with the rest of the country, both in economic as well as cultural terms”[3].

The date I have chosen as the symbolic beginning of the 1980’s is the year 1979, when the «Golden Bunch» devoted their entire symposium discussions to issues of shaping urban space, with a specific reference to Zielona Góra. The idea was to introduce and carry out the rules of the “Łagów Charter” [Karta Łagowska], a document which preceded the current discussion on city space by decades. The postulates made there were not feasible in the so called real socialism, as they assumed a specific impact of residents and artists on urban space, with much consideration for ecology.

The above was one of the reasons the so called Zielona Góra Program [Program Zielonogórski], which was to be introduced in a complex manner during the process of construction and reconstruction of the city, was never carried out. Its freedom-aimed aspirations, however, were blazing the trail for the events to come in August of 1980 – the actual beginning of the 1980’s.

The last “Golden Bunch” meeting took place the year martial law was imposed – the same year that BWA in Zielona Góra was closed.

In hindsight, the latter event seems significant now, to the effect that the authorities had completely forgotten to watch their image. At the time, however, it was already all about staying in power at any cost. This is, by the way, an example proving that sometimes it does not make sense to think in today’s categories, particularly those from the fields of marketing and public relations.

Based on the oral accounts, including one provided by Jan Muszyński, the director of the museum and the chronicler of the times, it seems that the closing of BWA was a consequence of the institution’s director, Wiesław Myszkiewicz, deciding to resign from membership in the Polish United Workers’ Party. He had returned his party membership card in protest against the imposition of martial law. Given the context, the end of the gallery seemed like revenge by the authorities. The army-imposed commissar issued a decree about the liquidation of the gallery, and all the employees, including the director, were transferred to work at the Museum. It could be said that it was the institution, and not the people who created it, that were subject to more stringent restrictions.

The decision to close the gallery was unprecedented in Poland, at least in the case of city-run institutions. It seems now that the entire situation was created to intimidate the artistic community, a way to show who was in charge. Only that the whole exercise was performed on the weakest player, as other institutions of culture were simply too big. As it turned out a year ago, the decision had been a mistake even in the eyes of the hardliners. The gallery was reactivated at the beginning of 1983.

The new chapter of its activities was to begin under the management of Marian Szpakowski. A resident of Zielona Góra for almost thirty years and one of the best known public figures in town. The artist decided to take the risk of entering into yet another relationship with the state authority. Basing my knowledge on oral accounts again, he was indifferent to any public criticism and accusations of being a collaborator. His priority was to build the institution a new, which would finally be independent of the Association of Polish Artists, and to save the “Golden Bunch”. This was the main reason he decided to accept the position. Judging by the list of exhibitions which were presented at the gallery when Szpakowski was in charge, the offer was rather local and without any more significant presentations. It seems that he did not have time to begin his own program – he died barely nine months after taking over the position of the gallery’s manager, unable to reach even the initial stage of reactivating the “Golden Bunch”. He failed due to the disintegration of the community, exhaustion of the subject, or absence of intellectual partners, among other things.

The problem, however, remained. After all, the «Golden Bunch» had for almost 20 years been a flagship cultural event in the city, though perhaps not as popular as the Soviet Song Contest. The latter was organized without any problems in 1982, and then continued to be successfully organized annually until the end of the decade. The contest, as it turned out, was easier to organize. A spectacular exhibition, on the other hand, was impossible without the involvement of specialists who, in the great majority, chose the strategy of “internal emigration” and refused any collaboration, or at least limited their activities to cooperating with the Catholic Church.

There was also the question of the Association of Polish Artists, which was suspended during martial law (and finally dissolved in 1983), its property handed over to PP Sztuka Polska, or new associations which were to take over those artists for whom membership in such organizations meant a secure basis for their material being. And so, 1982 marked the beginning of the disappearance of the institutional elements constituting the program and the basis for the “Golden Bunch”. The death of Szpakowski sealed the death of the project.

In 1983, two graduates of the art school in Poznań came to Zielona Góra, Zenon Polus and Zbigniew Szymaniak. Ambitious and knowledgeable about the art of their generation, they soon noticed that in the endeavor of trying to save the town from becoming the artistic boonies they were left to their own devices. The local artists at the time had either already gone beyond the period of exploring and participating in the avant garde of Polish art, had died (Szpakowski, Felchnerowski) or left the city (Kazimierz Rojowski, Ryszard Kiełb). Other young graduates of the academy who had begun to settle down in Zielona Góra in the 1970’s and 1980’s were not exactly inclined toward exploration, but wanted a peaceful place where they could do their own thing.

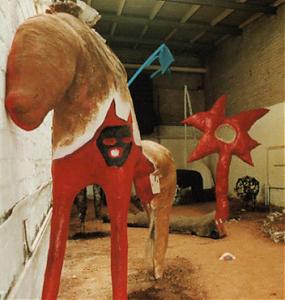

In the 1980’s, Zenon Polus created objects and installations, or used ready-mades. In his work, he analyzed the relations between nature and its cultural transformations. Zbigniew Szymaniak, on the other hand, was a painter first and foremost. As a result of his fascination with conceptualism, he had abandoned abstract art for hyper-realistic paintings inspired by semiotics. The first event the two artists organized was an exhibition titled Laboratories of the Young[Laboratoria Młodych], in the gallery of the School of Education [Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna], to which they had invited members of Łódź Kaliska and Jerzy Truszkowski, among others. The whole event only lasted as long as the opening night, with no documentation left behind. To Polus and Szymaniak the project was a test of their possible joint endeavors. The test was passed with the effect that the two artists decided not so much to reactivate the «Golden Bunch» but to organize a new project.

But the idea of continuation still had its supporters. In 1984, the new director of BWA, Bogumiła Chłodnicka, and artist Jolanta Zdrzalik paid a visit to professor Aleksander Wojciechowski, trying to persuade him to help them in their new undertaking. As it has been reported, he suggested that the event should be put on by young artists for young viewers. And so, those in favor of continuing the tradition and representing the old co-organisers of the “Golden Bunch” met Polus and Szymaniak in the office of the Party Secretary for Ideological Issues of the Voivodship Committee of the Polish United Workers’s Party, where the secretary, Zygmunt Stabrowski, unable to settle the dispute said: “The party can afford anything. Go ahead, create two events” (as reported by Zenon Polus). This anecdote, even if not particularly funny, is well reflective of the degree to which one had to interact and negotiate with the authorities to push one’s plans through. If it was not for the acceptance of their very existence (as it was not the program subject to approval, not directly at least), the event could not have been organized.

In the provincial though aspiring town of Zielona Góra, there was nobody to help the artists in their attempt at an independent organization of the event. Neither the colleges nor the church were able to support such an initiative. In case of the artists advocating the option of continuing the «Golden Bunch» tradition, there was nobody with charisma equal to that of the late Marian Szpakowski. And so, it was the enthusiasm, youth, and a good understanding of the art of the time that finally got the upper hand.

The “First Biennial of New Art” [I Biennale Sztuki Nowej (BSN)] was a project built on the idea that art should be more an area of agreement than division. The program was built with the help of respected authorities: Jan Berdyszak, Witosław Czerwonka, Jerzy Ludwiński, Andrzej Mroczek and Jerzy Treliński, whose task was to invite participating artists according to their own concepts. There were also young artists from the local milieu, invited directly by the organizers. The final result was an eclectic presentation which, for obvious reasons, did not encompass all the interesting artistic approaches of the mid 1980’s, but which still showed Polish art as a field which was very much alive and filled with an important reflection on art and the world. The stances there presented were of a whole variety – from post-conceptual proposals to painting and new expression sculpture.

There were no artists from Wrocław at the exhibition, which was definitely a mistake, considering the event was to offer a holistic presentation. This was partly due to the fact that among the invited authorities was Zbigniew Makarewicz, who had been expected to invite the Wrocław-based artists. In the spring of 1985, Brygida Grzybowicz and I went to see him. The reception was rather cold, our conversation looked more like an interrogation and pretty much led to nothing. In hindsight, I think I understand the reason for the reluctance and the fact that we were treated like security agents – after all, the meeting took place a year after the amnesty, as a result of which Makarewicz had been released from prison. In any case, the fact remains that there was nobody from Wrocław at the First BSN.

The final effect was, to my mind, quite spectacular. Over 70 artists presented their works at the BWA gallery, the Museum, Wenus cinema, the voivodship library, shop windows of the main department store, at the railway station, and in city space. There were also several performances, a theoretical symposium, all recapped in a catalogue, and abundant photographic documentation. The whole project was also an important social event, which served as a meeting opportunity for artists who had not really known each other’s work, since information did not run as quickly and efficiently in those times. The older and more acclaimed authors met those who had just had their debuts. Art dominated the city for three consecutive November days. The idea of a big event which activated a small community once again proved successful. Neither I nor my colleagues recall any pressure exerted by the local authorities, though there was some censorship – in the case of the exposition of Łódź Kaliska, the artists were ordered to remove the Mother of Jesus with a Mustache [Matka Boska z wąsami] by Adam Rzepecki, and a painting by Włodzimierz Pawlak, and A Stream of Russian Cologne [Strumień wody kolońskiej rosyjskiej] exhibited at the railway station (the artist refused to have only the caption removed as had been suggested by the censor).

The year of the Biennale was also when the gallery “po” was founded. Being an employee of BWA, I was responsible for the administrative organization of BSN, though I quickly began to interact with artists at the professional level as well. In the summer of 1984, I met a number of interesting people at the Plain-air Meeting of the Young in Łagów, including Fred Ojda, the manager of Galeria Działań from Ursynów [a district in Warsaw – from translator], Janusz Ducki and Zenon Polus. They persuaded me to consider creating a gallery in the rarely used small hall of BWA. After some months of hesitation and uncertainty, I was finally faced with the perspective of having to invite somebody to a partnership. The partner to be would have to be systematic, take responsibility for the documentation, and be cooperative and open to the dynamic course of events. That person was Leszek Krutulski-Krechowicz. The name of the gallery was borrowed from a text by Jerzy Ludwiński, who fully accepted our choice, though he didn’t really know us but still decided to trust us.

To start off, we would invite young artists from Zielona Góra, providing them with an opportunity to present themselves, but, on the other hand, testing our own organizational abilities. In the years 1985 – 1990, we organized approximately 70 exhibitions, performances, film screenings, and actions. We hosted such artists as: Mirosław Bałka, Edward Dwurnik, Jarosław Fliciński, Grzegorz Klaman, Zbigniew Libera, Antoni Mikołajczyk, Robert Rumas, Jerzy Treliński, Jerzy Truszkowski, Wojciech Zamiara, Witosław Czerwonka and many others who were just as important. According to its informal program, namely the text by Ludwiński, the gallery presented current phenomena which were sometimes difficult to classify, but which we accepted as their authors’ presented attitudes to life and art with which we could identify. In other words, we showed what we liked. Such criterion is perhaps not entirely professional, but it does give much satisfaction – it is more egoistic and social rather than artistic, but the final effect is pretty much the same.

The gallery was also a place which would attract those who wanted to meet the artists informally. There was no tension typical of opening nights, we tried to make the place friendly and unrestricted. In terms of the program, the gallery was complementary to what was on offer at BWA, presenting the really important phenomena in Polish art at the time. If not for the tolerance of the BWA’s director, Bogumiła Chłodnicka, the gallery would not have been able to function. Chłodnicka managed BWA in the years 1984 – 1989 and effectively carried out the ideas of Marian Szpakowski, though she was not part of the milieu herself.

Apart from being the organizer of BSN, our gallery was also involved in presenting the most interesting Polish studios in the different academies of fine art. This idea, first coined by Szpakowski, was born as a result of his discussions with Ryszard Winiarski and proposal to move part of the didactic process to a professional gallery. And so, the 1980’s saw presentations of the studios by, consecutively, Ryszard Winiarski, Jan Berdyszak, Wanda Gołkowska, Andrzej Dłużniewski, Jarosław Kozłowski and Witosław Czerwonka. The series was curated by Maria Jastrzębska-Szpakowska, a BWA employee since 1984 and the widow of Marian Szpakowski.

The studio presentations was an excellent but also pragmatic idea. Good exhibitions would be organized by the way (either in a plain-air meeting mode, or sometimes by means of ready presentations imported to the gallery), also showcasing the methods and ways of teaching art in the different schools. It was as part of this project that Zielona Góra first saw the new expression painting, presented in 1984 by Wojciech Dowgiałło and Wojciech Tracewski. It was also here that Robert Rumas carried out his first artistic concepts. As the city did not have an art school, the project also had added value in the sense that it showed the local residents the value such institutions could actually offer.

The Second Biennial of New Art [II Biennale Sztuki Nowej] was based on the well established fame of the first edition of the event, which was integrating and anticipating the role of new expression that had been so spectacularly presented at a much famed exhibition Expression of the 1980’s [Ekspresja lat 80-tych]. While the presentation by Ryszard Ziarkiewicz soon became a legend, the First Biennial is still awaiting a good description and an attractive recapitulation.

The second edition had a more determined profile than the first. The organizers invited non-official galleries, which Grzegorz Dziamski termed “alternative” in his introduction to the event’s catalogue. It was an attempt to define the notion of a non-institutional gallery in the understanding of the institutions of those times. The big no-show at the Second Biennial was Galeria Foksal, which simply turned out to be unattainable despite the numerous invitations.

All other galleries decided to come to the event – it is perhaps worth mentioning them all, if only to show the geography of Polish art in the latter half of the 1980’s: Warsaw - RR, Galeria Działań and Pracownia Dziekanka, Lublin – BWA, Poznań – Akumulatory 2, AT and Wielka 19, Wrocław – Foto – Medium – Art, Zakład nad Fosą, Ośrodek Działań Plastycznych, Łódź – Wschodnia, Chełm – 72 and Zielona Góra – “po”. The galleries invited were ones which had independent programs that also included some municipal institutions, as was the case of the BWA from Lublin. Managed by Andrzej Mroczek, it had become one of the most important galleries in the country, hosting conceptual projects and offering space for Polish performance art. Similar was the case of Galeria 72, which was part of the District Museum in Chełm and, under the eye of Bożena Kowalska, began to specialize in post-constructivist art.

As in the case of the First Biennale, the exhibition again happened in different places in town, each gallery having its own separate opening. Some of the openings were accompanied by performance actions. Again, the aspect of social interaction was very important during the whole meeting. Most of the presentations were related to New Expression which, at the time, was at the peak of popularity, both as a mode of illustration and a life attitude. Pracownia Dziekanka included presentations of the members of Gruppa and Neue Bieriemiennost collectives, Galeria Działań showed parts of the latter collective and works by the unassociated “New Savages”, and Wielka 19 exhibited “Grupa Koło Klipsa”. The galleries from Wrocław, on the other hand, were more focused on action-based and conceptual-related projects, which was also the case of BWA Lublin. Galeria Wschodnia concentrated mainly on the artists from Kultura Zrzuty. There is no place here to include a whole description of the exhibition – as I have already mentioned, we are still awaiting a monograph of BSN. In any case, when looking at the event from today’s perspective, it was an objective and extraordinarily broad presentation of the Polish art of the time.

The Third Biennial [III BSN] took place in November 1989, already after the first democratic parliamentary elections. The organizational committee changed, the exhibition’s commissioners were now Zenon Polus and Krzysztof Stanisławski who, apart from organizing their own exhibition, asked the following set of people to assemble the presentation: Witosław Czerwonka and Wojciech Zamiar, who invited young artists from the Tri-city area [Gdańsk, Sopot, Gdynia – from the transl.], Izabela Gustowska, who chose female artists only, Jarosław Świerszcz, who invited artists from Silesia, Andrzej Bonarski and Grzegorz Chełmecki, who decided on Tomasz Psuja, and Zbigiew Warpechowski, who went for artists from his home region.

In the introduction to the catalogue, Zenon Polus writes about: “a specific phenomenon, which emerged in the second half of the 1980’s, of the emergence of independent presenters, animators and authorities. The more or less expansive and thus anonymous organizations and programming committees are now being gradually replaced by concrete people who individually and openly embrace the risk of creating their own tastes and opinions about art” [4].

The 1980’s was actually the beginning of a rising wave of curators in the world of art. It is worth noting that the actual term used then was “exhibition commissioner” – the word “curator” did not appear until the following decade. The exhibition was supplemented with presentations of documentation portfolios of large exhibitions which were quite numerous in the second part of the 1980’s. The catalogue, which was never distributed due to the many mistakes and poor quality, contained summary texts by Grzegorz Dziamski, Krzysztof Jurecki, Krzysztof Stanisławski and Jarosław Świerszcz. I find these contributions extremely interesting: on the one hand they provided a very good insight to the approach towards the then new prospects appearing before Polish artists and, on the other, aimed at describing the current developments of the decade.

The Third Biennial was an exhibition of the time of the breakthrough. It tried to keep up, if somewhat nervously and without much success, with the accelerating reality. I remember it as a constant fight against the resisting matter and a continuous feeling of deficiency and inadequacy. The memory, however, is purely my own and quite unimportant.

The symbolic closure of the 1980’s for the art in Zielona Góra was marked by the opening of the art department at the local college (WSP, today Uniwersytet Zielonogórski). New and interesting artists began to flow into town, and the school started producing graduates. A drastic generational shift took place. The chief advocate and co-author of the new department was Zenon Polus – the school, therefore, was to a great extent the consequence of his curatorial and organizational activity of the 1980’s.

In the world of Polish art, Zielona Góra was both a model and an exceptional town. It was a model city for the medium size towns which did not have their own art schools and, therefore, no artistic communities which could afford any creative explorations. Such places were limited to events organized by local activists. The exceptional character of Zielona Góra, on the other hand, was related to its function of carrying on the legacy from times gone by, complicated relations with the authorities, the need to support the authorities in their efforts to sustain the myths about a cultural miracle and finally, of establishing an educational center which would be an important creative place, even if not up to the standards of an art academy. In Puławy, Koszalin, Elbląg – places of big cultural events of the 1960’s and 1970’s – such schools were never created.

From the present perspective we could say that the only platforms for building a sound artistic milieu in medium size towns are art schools, though the new department in Zielona Góra was not very helpful in provoking a new reflection on the 1980’s – no important research of the events of the decade was ever carried out. The whole ten years is left without a descriptive, not to mention a critical, analysis, which reveals the weakness of the local abilities on the one hand and, on the other, their being suspended in a social vacuum. All the events which are significant in the eyes of art history are pretty much non-existent in the collective memory of even such a relatively small city. They have been abandoned on the margins of the course of things. The situation provokes questions about the general functioning of myths, but also leads to bitter reflections on how to keep a memory alive. We have failed to keep that memory alive in Zielona Góra.

Perhaps the art departments at the local university are a non-verbal way for the myth about the forgotten events of the past to continue. The myth remains unrecorded, still awaiting its demystifier. It is yet another poorly known episode in our history.

Wojciech Kozłowski, a critic and curator, director of the BWA Gallery in Zielona Góra, in the eighties - together with Leszek Krutulski-Krechowicz – he ran the “po” Gallery at the BWA in Zielona Góra.

Notes

1. Quote after: Luiza Nader, “Konceptualizm w PRL”, Warsaw 2009. ↑

2. Konrad Schiller, “Struktura sympozjalna ‘Złotego Grona’ w Zielonej Górze w latach 1963-1981”, MA dissertation thesis written and the Art Institute Department of the Warsaw University under the supervision of Prof Waldemar Baraniewski. ↑

3. Ibidem. ↑

4. “II Biennale Sztuki Nowej”, exhibition catalogue, ed. Zenon Polus, BWA (Zielona Górze 1989), catalogue undistributed. ↑