Luiza Nader. Shame! Socialist Realist Historiography in the 1980’s. (case study)

In a publication of major importance to art history in Poland, „Sztuka polska po 1945 roku” [Polish Art After 1945], which appeared in 1987 and compiled the papers delivered at a session of the Association of Art Historians in November 1984, Waldemar Baraniewski proposed an extremely insightful take on the fascination evoked by socialist realism in the late 1970’s, which became even stronger in the 1980’s:

“Socialist realism is ‘in’. Twelve years have passed since the first confrontation of socialist realist works with contemporaneity (Kassel, 1972). Recent years, however, have brought about an acceleration in the research on socialist realism, not only in Poland. Since the late 1970’s ‘soc’ is becoming increasingly popular. In 1979, a painting exhibition took place in Kazimierz Dolny. The March issue of Sztuka from 1980 contained a series of texts on socialist realism; a whole number of M.A. and Ph.D. dissertations are devoted to the subject, and students demand of their professors to teach them about socialist realism. In other words, the subject has become really hot. Even in the volume of this session, socialist realism has been referred to in almost every article – something that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. What are the reasons for the situation? Apart from the clearly cognitive and extreme cases of perverse curiosity, the problem seems to be more complicated. It seems to me that it has been very much touched with the spirit of postmodernism, but there has also been an increased interest in all the issues from outside of the domain of art – from the sphere of attitudes, entanglements and ideological choices”[1].

In the present text, I would like to focus on the sphere of “attitudes, entanglements and ideological choices” made by the historian in the 1980’s vis-à-vis the subject of research of such affective engagement, namely socialist realism. I would particularly like to dwell on the exchange of affects between the researcher and the subject of his explorations, carried out at the textual level. Was there indeed a shift in the research on socialist realism in the 1980’s? If so, had it anything to do with the challenges and tensions in art and historiography taking place at the time? In my deliberations, I intend to concentrate on the book by Wojciech Włodarczyk published in 1986 “Socrealizm. Sztuka polska w latach 1950–1954” [Socialist Realism. Polish Art in the Years 1950 – 1954]. The questions I plan to ask touch on the way that socialist realism has been constructed in the mentioned work as a subject of analysis. How is the work of transfer, as performed by the researcher, decisive in his/her research strategies? What is the influence of the research paradigm, present in the publication above, on contemporary art history? I am also interested in affects which are combined, trasmitted and transformed by this specific text from art history in reference to the reflection on socialist realism of the 1980’s[2].

In the contemporary analyses of the history of Central European art, Stalinism (whose cultural derivative was socialist realism) is treated as the founding traumatic event in the area of visual arts[3]. The experience of socialist realism has been termed of key significance to the art after 1945, having a decisive effect on things like the understanding of the notion of autonomy, politically engaged art, or the question of resistance. During the period of the “thaw”, with the art criticism and history that entailed in Poland, socialist realism was considered – to use the terminology offered by Jacek Bocheński – in categories of a “void space”, a closed chapter which should be forgotten about as quickly as possible, moving on to business as usual and seeking a continuation of the “progressive tradition”, recovering the “natural” courses of modern art which could be distorted should socialist realism develop[4]. At the same time, socialist realism was seen as an experience of ruthless violence, stretching beyond any possibilities of defence and protection of the sovereign decisions of the subject.

The responsibility for socialist realism has been shifted onto its participants, rather clearly drawing the line between the relentless ones, meaning representatives of the avant garde, and the avowed socialist realists, though the diversity of the artists’ attitudes towards socialist realism was not analyzed (and neither was socialist realism, for that matter).

Until the beginning of the 1980’s, art history had perceived socialist realism as bad art or (to quote Aleksander Wat), as non-art. It was thus treated as a chapter left neglected, unwritten or dealing with a time halted[5]. Until that time, it had been seen by both critics and artists (with few exceptions) as a phenomenon which should be erased or (at least) exiled to oblivion. The connotations evoked by socialist realism were only negative. As a result, art promoting direct political involvement was met with aversion. The situation of artistic practices with the ambition of political and social transgression became complicated and the position of figuration and realism was turning ideologically ambiguous. The ideological and visual associations with socialist realism led to a critical assessment of, for example, Jan Świdziński’s contextualism, as was also the case with an earlier work by Wprostowcy. In the 1980’s, another term was coined “sacr-realism” to denote the art presented at exhibitions organised in church premises, which was termed as such for reasons of poor artistic quality verging on kitsch, but also due to its figurative and literary character[6].

Socialist realist art began to attract broader attention in the late 1970’s. In 1979, the exhibition Malarstwo kształtowania się władzy ludowej w polsce 1949–1955 [The Art of Painting That Formed the Authority of the People 1949 – 1955] (Galeria Letnia, Muzeum Kazimierza Dolnego) was organised, which served as a reference to the text published a year later in Sztuka (no 3/7/80) by Stefan Morawski, Teresa Kostyrko and Anna Zeidler (the catalogue to the exhibition also contains a sketch of hers)[7]. It should also be noted that the opinions which were to initiate the discussion on socialist realism as a result of the growing interest with the subject were rather apologetic in tone (especially the paper by Stefan Morawski); the authors dwelled on socialist realism in absolute detachment from the totalitarian context, neglecting the opressive nature of the field of culture of the 1950’s. Instead, they saw it as a direction in art which may have failed due to different “mistakes and distortions” but which still offered hope.

Such tone came to a definite end with the change in the political situation in Poland: workers’ strikes and the events of August 1980. I think that it was actually true for the entire culture in Poland at the time. It was the beginning of settling accounts with childhood – both one’s own, as well as that of the system, whose early years were those of Stalinism. 1981 saw the making of such films as The Little Pendulum [Wahadełko] by Filip Bajon and The Shivering [Dreszcze] by Wojciech Marczewski[8] ; censorship restrictions were lifted in case of Hands Up [Ręce do góry] by Jerzy Skolimowski (1967), even though the film was not released for complete distribution. Of course the most spectacular return to socialist realism was Man of Marble [Człowiek z marmuru], 1976, by Andrzej Wajda.

The first opinions about socialist realism, which were tainted with revisionism, included those voiced by, again, Andrzej Wajda, as well as Witold Lutosławski (as well as Andrzej Braun and Tadeusz Kantor) at the Congress of Polish Culture in December (11-13 December) 1981. The objective of the Congress was to deliberate on the current condition of Polish culture and to outline the challenges and prospects of its development in light of the new social situation caused by the workers’ strikes and the August 1980 accords[9].

Socialist realism was a notion present in the interventions and discussions, seen as a problem which called for re-evaluation in face of the new political situation. In an address to the other speakers and also in response to the postulates of the Congress (i.e. assessment of the state of culture and its directive function – how to build culture for the future), Anda Rottenberg had prepared a text, which she never delivered, as on the third day the Congress was dissolved as a result of the imposition of martial law[10]. The text, however, seems extremely important, though it remained inactive at the time. Its importance stems from the fact that it reconstructs the type of knowledge that Michel Foucault called savoir: of quotidian discourses, practices, procedures and institutions, the rational and irrational terms and sources from which the formalised 80’s knowledge (or the connaissance) about socialist realism took its beginning[11].

Rottenberg’s text introduced completely new notions to art history which remained vibrant throughout the entire decade of the 1980’s and which were related to the interlocking of political and cultural events from the beginning of the 80’s, focusing again on the period of socialist realism. It was a settling of accounts, however, not with the builders of socialist realism but with the generation of Anda Rottenberg, who had internalised socialist realism, having experienced it in childhood. According to Rottenberg, the experience of socialist realism resulted in a state of eternal childhood, incapacitation, suspension of responsibility. The author offered the thesis that socialist realism should not only be seen as a closed chapter, but that it was a destructive experience which continues to impact the culture and consciousness in Poland. When referring to contemporaneity, namely the early 1980’s, Anda Rottenberg stressed that she was interested in the artistic expressions which were not so much challenging socialist realism as its mnemonic experience.

I see this text as extremely significant because it shows socialist realism not as an external phenomenon but an internal experience, limiting and determining the identity, a work of the memory, the ethical and esthetical choices of subjects in the 1980’s. The right to self-determination by settling accounts with one’s own memory of socialist realism has been particularly highlighted here. Such memory can now be interpreted as being saturated with the affect of shame of the post-socialist realism generation. This „post-generation” cannot feel responsible for acts it had not committed. In its feeling of shame about the memory of socialist realism, these people can only seek solace by both trying to look for answers and ethical responsibility for the time in which they live.

Socialist realism, with its genealogy, cultural and social effects, as well as the attitudes it evokes, is also a subject of interest to younger researchers on the early 1980’s - Wojciech Włodarczyk, Waldemar Baraniewski, Maryla Sitkowska, Anna Zacharska or Jerzy Ilkosz. When martial law was imposed, Anna Zacharska and Maryla Sitkowska withdrew from the opening of an exhibition, The Faces of Socialist Realism, organised in March 1982 at the National Museum in Warsaw. The presentation did not take place until 1987, and when it did, it turned out to be one of the most important events of the decade.

In November 1984, the already mentioned session of the Association of Art Historians took place, where in almost all the texts socialist realism was referred to as an experience requiring a rethinking and revisiting, a phenomenon redefining the entire avant-garde tradition and the notion of modernity. The volume with the session’s materials, published as late as 1987, still remains one of the fundamental readings for a contemporary art historian[12]. The publication includes such texts as “The Polish Ideosis” [Polska ideoza] by Andrzej Turowski, “Modernity and Its Limits” [Nowoczesność i jej granice] by Wojciech Włodarczyk, “On Socialist Realism” [Wobec realizmu socjalistycznego] by Waldemar Baraniewski, “Puisque réalisme il y a” by Elżbieta Grabska, and an afterword by Mieczysław Porębski – to mention just a few which have referred to socialist realism, and which, at the same time, are very much embedded in the specific political situation of the 80’s.

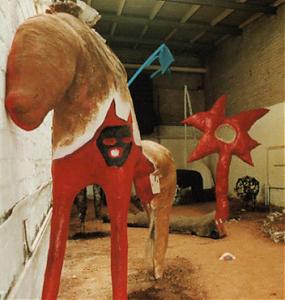

Such juxtaposition of both the art and the cultural field which had created it of the late 1940’s with that of the 1980’s was also proposed by Ryszard Ziarkiewicz at the exhibition Paradise Lost – Polish Art in 1949 and 1989 [Raj utracony. Sztuka polska w roku 1949 i 1989]. Though the presentation took place at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw already in 1990, its comparative idiom and curatorial perspective was deeply rooted in the discussions of the 1980’s[13].

In 1983, Wojciech Włodarczyk defended his Ph.D. thesis “Polish Art in Times of Socialist Realism” [Sztuka polska w latach realizmu socjalistycznego] which he had written under the supervision of Prof Mieczysław Porębski. The thesis was later published in book form by the French publishing house Libella, under the title “Socialist Realism. Polish Art in the Years 1950-1954” [Socrealizm. Sztuka polska w latach 1950–1954][14], and has become a source of reflection about socialist realism in Poland in the times that followed: both in the 1980’ and 1990’s as well as in the last decade.

Socialist Realism: the Guilt and Disgrace of the Avant Garde

The question which I attempt to seek an answer to in my modest reading of the book is: what is the reaction between the critical and the symptomatic in the book? How can these relations be useful[15]?

First of all, Włodarczyk included socialist realism among other trends in 20th century art. Analysed not as “nothingness” but as a cultural phenomenon which can be subject to formal analysis, the author reconstructed socialist realism in the sphere of artistic decisions and choices. In his research, Włodarczyk not only worked on creating an image of socialist realism but also tried to explain the horizon of post-war art in Poland, including the art of his time, in light of this newly revisited phenomenon. It may be said that the motto of the book is the words by Jan Józef Szczepański: “it is impossible to understand contemporaniety without understanding the Polish conscience and consciousness of that period”[16].

The Subject of Research: Socialist Realism as the Reverse of the Avant Garde

The detailed analyses proposed by the author result in a presentation of socialist realism as pure formalism, as mechanisms of esthetical choices made on canvas. Włodarczyk highlights the phatic functions of socialist realist painting, at the same time negating the persuasive ones, indicating its elementary traits, which are non-transparent and arbitrarily determined, such as ideology and the national form. He takes apart the image of socialist realism, stressing its stylistic diversity and, at the same time, certain virtually impossible theoretical assumptions which caused the socialist realist painting practices to fail: the extraordinarily codified creative process, as well as the supremacy of the order of the composition, which assumes that all the elements of the formal code should be balanced.

The author outlines the genealogy of socialist realism, reaching back to 19th century realistic painting and proletariat culture. Most of all, however, he traces the affiliations and analogies between socialist realism and the avant garde and reconstructs the historical circumstances as well as the ideological foundation thanks to which socialist realism could be not so much imposed but accepted in Poland. This is why the book, “Socialist Realism […]” [Socrealizm. Sztuka polska w latach 1950–1954], has become not just an analysis of the socialist realist works, theories or directives, but, first and foremost, a huge exercise in settling accounts with the ethos and practices of both the historical, as well as the contemporary avant garde.

And it is the avant garde (Włodarczyk completely accepted its definition as proposed by Renato Poggioli), with its ethos of participation, social and political change, as well as historical determinism that, by means of its connections with radical political circles in the 1930’s, turned out to be the destructive power that determined the success of socialist realism. (p. 74). Włodarczyk believed that the avant garde adhered too much to the notion of the artist’s high social status, and that its concepts of political art left artists harmless against socialist realism (p.134). Then again, in the period of the thaw, as Włodarczyk continued his critical thesis, it was the representatives of the avant garde who contributed to wiping socialist realism from the memory, seeing it as emptiness, nothingness. Hence it was the avant-garde formation responsible for effectively discouraging artists from trying to settle accounts with socialist realism, leading them to fall into the hermetic meanders of intrinsic art (pp. 77, 146).

The criticism of the avant garde on the pages of Włodarczyk’s book grows gradually to finally explode with full force at the end. It is not actually the proposed analyses of socialist realism but the criticism of avant-garde ideas which give the text a narrative cohesion, releasing its affective impact. Though its title may suggest so, the book is not a description of socialist realism as a holistic phenomenon, rather an illusion of such. The publication is compiled of fragments which, in a sense, are socialist realist margins. Such nature would be to the book’s merit if the author had problematized these issues, giving them methodological value. Instead, the researcher imposes a model of logical deduction on the historical reality. At the same time, he unfolds an extremely rich, though rhetorically subtle, narrative: he makes use of different types of ellipses, allusions, hyperboles, effects of gradation and suspension. A huge challenge that, to my mind, calls for a separate analysis, which I cannot afford here, is a rhetorical study of “Socialist Realism […]” - a study of the authenticity of statements applied in the historical narrative as an effect of rhetorical figures.

The most spectacular example of rhetorical operations present in the book by Wojciech Włodarczyk is the figure of socialist realism as a hyperbole of the condition of modernity in Poland. The effects of gradation and suspension are used predominantly in reference to the question of the responsibility of the avant garde for socialist realism, bearing in mind that the trick gives the narrative a dynamic tempo and articulation. The gradation related to the repetition and the inversion of meaning is particularly visible, if only to mention the example of the numerous quotes or references to the same statement of Maria Jarema about the uncertainty of her own silence about socialist realism (pp. 59, 68, 76). Figure of speech is used here to reinforce the persuasive aspects of the text in its evaluating layer which, in this case, refers to the negatively interpreted ambiguity of the representatives of the avant garde vis-à-vis socialist realism.

The abundant spectrum of the rhetorical figures drawing on the mission and the need for apposition (allusion, ellipsis, as well as hyperboles which assume a shared knowledge of the author and the reader about what has been exaggerated) seem to indicate that the author is addressing those readers who are close to him in terms of culture and outlook, hence who are able to decipher the language. Such readers are also able to understand the hierarchy of values adopted by Włodarczyk, at the peak of which stands the assumption that the current of art runs independently of the current of politics (p. 60).

This community of communication between the author and the recipient, however, also bears ideological consequences. The philosophy applied by Wojciech Włodarczyk is more one of justification rather than argumentation. It is a discourse of authenticity which does not allow for controversy, uncertainty, clashes of standards of knowledge or truths[17]. Hence the assumption of a cognitive and ideological horizon which is common to the author and the reader. To the author of “Socialist Realism […]”, history is of a processual character which is also sequential and rational, based on solid subjects and facts. It is not a vision of history as “an infinite number of entangled events”, which result from a „multitude of mistakes and fantasies”[18]. Włodarczyk’s version of history is stuck in a supra-historical regime, guaranteeing a fantasmatic diagnosis of the state of culture, a ruthless historical assessment which is also performed by the reader.

The Transference

Włodarczyk recognizes the complicated position of a researcher studying socialist realism and the extraordinary entanglement in the object of the research that it entails. The task calls for a synergy but, at the same time, a fluidity and transferability of positions between the researcher and the subject of his/her study.

The author writes: “The continued vitality of the issue of socialist realism is generally an obstacle in studying this current, placing the researcher in a peculiar situation, especially in Poland. […] No researcher can ‘pretend’ that he/she is at a difficult to determine distance from the object, […] in a safe area of expertise, where his/her work is not distorted by error, limitation or prejudice”. A researcher of socialist realism, however, is particularly entangled in these “errors, limitations, or prejudices”. The entanglement stems not so much from the specificity of the very subject of the research as from the special conditions in which the “solitary” artist in the Stalinist era existed, and which are not alien to the researcher”[19].

Thus Włodarczyk very ably describes the phenomenon of transference, which, in the historiographical studies of Dominick LaCapra, is seen as one of the decisive ones[20]. In historical research, such transference is understood as engagement in the subject of research with the tendency for repetition in the discourse or in the practice of the content present in the object or projected onto it, e.g. the repetition of the mechanism of the “scapegoat” in the studies of the phenomenon or the replication of Nazi terminology in the analysis of Nazism[21]. As La Capra indicates, the historian is obliged not so much to seek an external point in reference to the transference as to demolish it by means of description and analysis.

The author of “Socialist Realism...” is only partly successful in this operation. On the one hand, he does recognize the disturbing community of experience now and then, for example, when he describes the phenomenon of the existential solitude which was the common denominator of the cognitive horizons of the socialist realist artist and the researcher of the art of the 1980’s. On the other hand, however, he is too quick to give up on analyzing his subjective position and this disturbing feeling of proximity. He decides on finding a fantasmatic external vantage point from which one could see all the political, social and national circumstances of socialist realism which had forged it (p. 9). As the author writes, his point of view would correct the distortions stemming from the structure and nature of the doctrine itself.

Thus Włodarczyk places himself in the position of the omnipotent Self, who is beyond politics, society, or memory. Such position does not protect him but exposes him to transference: the researcher repeats the valuating judgments present in the very ideology of socialist realism – the total depreciation of the avant garde and modernity – creating a negative myth of the avant garde. Neither in his vision of history does Włodarczyk escape the pitfalls of historicism, which he sees both as one of the most important elements of both poetics, as well as the ideology of avant garde and socialist realism. The chopping up of socialist realism into periods, with a distinguished initial phase, then a time of high development, and finally a decline, is a typical organic metamorphosis of the historical time. But if socialist realism meant the end of the avant garde and, at the same time, it was a “key” experience of modernity, it thus determined its structures completely.

These are visions of history which are also close to the notions of finalism and fatalism. Socialist realism grows and dies like an organism (its death turns out to be necessary), and the space of the field of culture in Poland is totally marked with socialist realism. Furthermore, failing to refer to this experience forecasts the decline and the end of a given cultural formation. The further the artistic practice and reflection is from socialist realism, the closer the symbolic death (in the context of “Socialist Realism...” it referred to the avant garde, while in another text, “Modernity and Its Limits” [Nowoczesność i jej granice] it concerned modernity). It could be said that the temptation of socialist realism is also felt here by the researcher, who is at the same time lured and repulsed by it.

The existential category blurring the divisions between “now” and “then” which the author sees, following Hanna Arendt, as one defining social life in totalitarianism, is loneliness (p. 6). In this case, loneliness is understood as the solitude of the subject which has been disinherited from both the public and private domains, deprived of cultural and social identity, with an exhausted ability to participate in politics. The category of “existential solitude” can be compared to the category of “generational incapacitation” which Anda Rottenberg introduced to the area of art history (following Andrzej Kijowski, who had used the concept of incapacitation in reference to the condition of literature in the 1970’s 4). Such description of the condition of the subject seems to be dramatically apt in response to the need, and at the same time an aporetic challenge, for both critics and artists in Poland in the 1980’s[22], to redefine one’s Self (understood not only as a mental reality, but also as a professional identity) vis-à-vis the political framework.

Transcending the solitude and incapacitation by freeing the traumatic memory and opening up one’s subjectivity, exposing it to the disturbing otherness (e.g. to research on socialist realism) are all challenges which Włodarczyk recognizes the complicated position of a researcher studying socialist realism and the extraordinary entanglement in the object of the research that it entails. The task calls for a synergy but, at the same time, a fluidity and transferability of positions between the researcher and the subject of his/her study. The author writes, the intellectuals had to face when clashed with events of August 1980: solidarity, community, togetherness. It also meant the challenges that the society had to face after the imposition of martial law: shock, boycott, active resistance.

History, Guilt, Shame

Włodarczyk reconstructs socialist realism as a process of seduction and subordination of artists who yield to the authority and its directives. He does not take into consideration, however, that seduction does not exclude violence and force. All those who decided to join socialist realism were, in the author’s view, opportunistic, while those who fell silent were driven by fear. The avant garde in Włodarczyk’s book has been exposed in its fantasy of being a socially engaged art, with a dream of a communication utopia and political transgression. A mise en scène is created by the text, where one of the main characters – the avant garde – is facing the social and political challenges of both the 1950’s, as well as the entire post-thaw culture, including Solidarity and martial law, and as such is unable to cope with it all. The avant-garde temptation of socialist realism and, at the same time, the uncertainty or lack of participation in socialist realism, is a step forward which is morally right –it is unmasked and exposed.

The gesture of exposing, unmasking and publicly revealing the inadequacy is connected with the affects of shame and guilt which, for a long time, had been seen as transitive categories. As Ruth Leys, specializing in researching affects, writes, shame is motivated by external circumstances and the infringement of social norms and, as such, refers to the condition of the subject, i.e. myself and my imperfections. Guilt develops both in relation to the actual past actions, as well as to fantasies about them; it can be a reaction to transgression; it is associated with the need for and expectation of compensation[23].

Włodarczyk’s book, it is the avant garde which is made responsible for the ideological foundations giving rise to socialist realism, and shamed for failing to recognize its effects, as well as for keeping silent about it (the author believes that the silence was also driven by fear), for not experiencing it, and for not settling accounts with it. Here, socialist realism is presented by Włodarczyk as a temptation while the avant garde – regardless of the effects (be it of participating in socialist realism or keeping silent about it) – is shamed for its susceptibility to temptation, its fantasy about temptation. The researcher does not consider these affects directly but merely hints at them, transmitting them via the text. They are revealed by the rhetorical and ideological stratum of the text, e.g. in sentences such as this: “The foundations of avant garde, taken to the absurd in socialist realism, were widely introduced owing to the specificity of the 1930’s. They became commonly accepted – a bitter experience for a 20th century artist. […] In Poland, socialist realism did not last long. It was avidly accepted, though often as a result of sheer calculation” (pp. 146 – 147). In this case, the persuasive functions were assigned not so much to argumentation as to the rhetoric of the text, with the application of gradation and use of highly evaluative vocabulary[24].

It is the author of the book who actually makes the judgment about avant garde, with the reader’s task to blame and shame avant garde for socialist realism. The guilt and shame presented in Włodarczyk’s book as affects are also a means of judgment, valuated negatively. They are, at the same time, ethical and political: their role boils down to settling accounts, cleansing, pointing at the guilty ones. They are also there to recover self-identity, though it is done by means of “exteriorizing evil” – distancing the described phenomena from, for example, writing art history. It is more a process of shaming than feeling ashamed. However, what other positive use could be made of such relations?

As Ruth Leys notes, shame is an affect of the helpless, it stems from social inequality and injustice, it does not have to be valued negatively. On the contrary, the introduction of the category of shame (in contrast to the category of trauma) bears fruit by recovering subjectivity, sovereignty, and responsibility – what Włodarczyk actually does. It brings to light its own subjective fragility, the permeability to the subject, its vulnerability to affective transmission. Furthermore, it has a potential to formulate a new subjectivity, giving hope for change[25]. Douglas Crimp noted that one should differentiate between the moralistic use of the affect of shame (shaming) and its ethical and political application. In the latter case: “In the act of taking on the shame that is properly someone else’s, I simultaneously feel my utter separateness from even that person whose shame it initially was. […] Thus, my shame is taken on in lieu of the other’s shame. In taking on the shame, I do not share in the other’s identity. I simply adopt the other’s vulnerability to being shamed. In this operation, most importantly, the other’s difference is preserved. […] In taking on or taking up his or her shame, I am not attempting to vanquish his or her otherness. I put myself in the place of the other only insofar as I recognize that I too am prone to shame”[26].

Following Eve Sedgwick, Crimp highlights the performative nature of shame in its double meaning: as a spectacle that requires a stage, and in the categories of the Austinian theory of acts of speech. If we were to transpose Crimp’s observations to the level of writing history, we could assume that such a take on shame is possible when it is not understood as a unilateral operation of shaming, but when it also reveals its affective nature to which all subjects of the scene (which is historical, in this case) are susceptible: both the subjects which are subject to analysis in their actions, attitudes or decisions, as well as those which construct a narrative and make judgments. The shame, which assumes (if only fantasmatically) the experience of being visible, inflicts and permeates (in this case) all the instances of a historical performative (the historian and the events he/she describes, as well as the reader) leaving them in a state of ethical uncertainty and anxiety as to their own decisions, stances, and choices made in extreme situations.

The book by Wojciech Włodarczyk served the function of evoking shame in the avant garde: settling accounts not so much with the socialist realists, but with the neo avant-garde formations, in particular with the modern (modernist) culture drawing on avant-garde tradition, which underwent a serious crisis in the 1980’s – not only in Poland, but also in the western culture. The root of the cause was, on the one hand, the appearance of contradictory post-modernist theories in art history and cultural research (the so called “post-modernism of resistance” seeking ruptures and aiming at disarming modernism, and conservative post-modernism, which aimed at historicising and rejected the experience of modernity). On the other hand, however, it was also due to the spectacular comeback of the medium of painting.

In the case of Polish culture, the two threads inevitably lead to the question of the artists’ responsibility vis-à-vis the very expressive political reality, about the possibilities of construction via art and the history of gestures of resistance. I believe that it is the reflection on socialist realism and the avant garde, as well as its immanent dispute with the formation of modernity, which should be interpreted as the gesture of resistance. Socialist realism, which was continuously promoted by the regime-supported exhibitions, such as the anniversary presentation of the works of Helena and Juliusz Krajewski (Zachęta, December 1985) or Budujemy nowy dom... Człowiek i praca w sztuce realizmu socjalistycznego (Muzeum Okręgowe in Lublin, 1987/1988) and, at the same time, pushed into oblivion by the artists, was for those reasons a challenge in the 1980’s though, at the same time, it also became a part of the critical cultural production which had to resist the attempts to strip it of value and identity (the attempts made by the then cultural policy of the state in the 1970’s).

All these vectors: the 1970’s with their extremely pessimistic diagnosis, the formation of the free trade unions and Solidarity between August 1980 and 13 December 1982, the need for cleansing and action, martial law, the boycott of official art institutions and media and, on the other hand, the post-modern climax and the depreciation of the achievements of the avant garde stemming from its conservative currents, constitute a grid of tensions to which the book by Wojciech Włodarczyk was also subject.

The Omitted Paradigm

Thanks to Wojciech Włodarczyk’s publication, socialist realism in Polish historiography changed from an “empty phenomenon” into one of far-reaching cultural consequences, into an active space impacting the nature and shape of Polish art after 1955. By constructing the memory of socialist realism, the book was also instrumental in establishing a certain mode of knowledge based on which it was not the war, but socialist realism which became the key experience for art and culture in Poland (it is particularly explicitly expressed on pages 74-75). In an attempt to describe the „consciousness”, “conscience”, and “mechanisms of making choices”, the author completely lost sight of the reality of the 1940’s as a “world after a catastrophe”, both civilizational and cultural, and, in the case of Poland, also moral. He writes that the “civilizational anxiety evoked by social changes and colossal technological development” (p. 67) was the main subject and problem of art in Poland in the latter half of the 1940’s.

The rejection of the war as a turning point, which resulted in the significant omission of the Holocaust, as well as the elimination of “absolute moral devastation” from art history, and a revisionist attitude towards the period of socialist realism (with the caveat that the revisionism applies to both the active participants of socialist realism, as well as the artist who had remained silent at the time), make for a paradigm which has been to a great extent constructed by the art historiography of the 1980’s.

I believe, however, that the avant-garde shame as we see it in Włodarczyk’s book (the ideological responsibility for socialist realism) or the sin of engagement (participation in socialist realism) cover up a problem which is much more significant. In the eyes of the researcher, guilt and shame do not have to, but can mutually overlap in terms of their mechanisms with the logic of trauma. Therefore, if both these affects are to be treated in a traumatic manner (which would however entail a relegation of the subjective responsibility), it must be remembered that for a trauma to appear, there needs to be two of them. What is it that is covered up by guilt and shame, by this trauma of socialist realism that art history in Poland was so willing to absorb? I dare say that in this case, the engaged trauma is covering up the trauma which is not engaged, namely the post-war indifference of artists in Poland (I mean not the survivors but the observers of the Holocaust) to the Holocaust, as well as the absolute absence of reflection on the issue in Polish art history, which never tried to revisit its courses, hierarchies and canons vis-à-vis this event.

And if we were to give up on the trauma-based interpretation, then the guilt and shame which the researchers grappled with in the early 1980’s was actually the socialist realist past, while the challenge that the contemporary art history in Poland has to face is the absolute indifference of our discipline, in its domestic version, to the Holocaust and the suffering of the Other[27].

Every age has its challenges. It is not the revision of socialist realism, the memory of which has been domesticated thanks to the researchers of the 1980’s, but painful reflection on indifference, the position of the observer – the one who is a shameless onlooker of the suffering of others – which is the challenge of contemporaneity. A valuation of shame, an analysis of one’s subjective position and, at the same time, a recognition of the affective aspect of the narrative by the subjects writing the history would, to my mind, be very much called for.

Luiza Nader, born in 1976, art. historian, lectures at the Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw. In 2005 she received a Fulbright scholarship. Published book – “The Conceptual Art in the Polish Peoples’ Republic” (2009). Her main focus is on avant-garde and neo-avant-garde art, particularly in Central Europe, as well as on relations of memory and archives, theories of trauma and affect.

Notes

1. W. Baraniewski, “Wobec realizmu socjalistycznego”, in: “Sztuka polska po 1945 roku. Materiały sesji Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki”, listopad 1984, (Warsaw 1987), pp. 186–187. ↑

2. I would like to take this opportunity and extend my great many thanks to Karol Sienkiewicz for his invaluable help in writing this text; his very generous offer to let me use his library search results on exhibitions and critical texts about the re-emergence of the interest in socialist-realism in Poland of the 1980’s. ↑

3. See P. Piotrowski, “Awangarda w cieniu Jałty”, (Poznań 2005). ↑

. In this context Piotr Juszkiewicz points to the exceptional stance of Mieczysław Porębski, see P. Juszkiewicz, “Od rozkoszy historiozofii do ‘Gry w nic’. Polska krytyka artystyczna czasu odwilży”, (Poznań 2005). ↑

5. See A. Kępińska, “Nowa sztuka. Sztuka polska w latach 1945–1978”, (Warsaw 1981); B. Kowalska, “Polska awangarda malarska 1945–1970. Szanse i mity”, (Warsaw 1975). ↑

6. The controversy surrounding the Wprost collective is also taken note of by W. Włodarczyk, “Lata 80.: sztuka młodych”, Warszawa 1990. The terms “sacr-realizm” appears in a text by Marek Skwarnicki, “Sacr-realizm”, Tygodnik Powszechny, 12 Jan 1986, no 2 (1907), p. 8. ↑

7. S. Morawski, “Utopie i realia”; T. Kostyrko, “Realizm socjalistyczny – o niektórych źródłach jego niepowodzeń”, A. Zeidler, “Malarstwo realizmu socjalistycznego – tradycja czy historia?”, Sztuka no 3/7/1980, pp. 17–28. ↑

8.The issue of childhood at the beginning of the 80’s and the two films were highlighted by the two excellent editors of the book Przeciąg by Anda Rottenberg, Kasia Redzisz and Karol Sienkiewicz in a footnote no 2 to the text “Dla kogo ten kongres?”, in: A. Rottenberg, “Przeciąg. Teksty o sztuce polskiej lat 80.”, (Warsaw 2009), p. 81. ↑

9. “Kongres Kultury Polskiej: 11–13 grudnia 1981”, ed. W. Masiulanis, (Warsaw 2000). ↑ ↑

10. A. Rottenberg, “Dla kogo ten kongres?”, in: “Przeciąg”, op. cit., pp. 77–81. ↑

11. J.J. Scheurich, K. Bell McKenzie, “Metodologie Foucaulta. Archeologia i genealogia”, in: “Metody badań jakościowych”, ed. N.K. Denzin, Y.S. Lincoln, t. 2, (Warsaw 2010), pp. 294–295. ↑

12. “Sztuka polska po 1945 roku. […]”, op. cit. ↑

13. “Raj utracony. Sztuka polska w roku 1949 i 1989”, ed. R. Ziarkiewicz, (Warsaw 1990). ↑

14. W. Włodarczyk, “Socrealizm. Sztuka polska w latach 1950–1954”, (Paris 1986). ↑

15. I ask this continuously important question following Domick LaCapra, see. D. LaCapra, “Rethinking intellectual history and reading texts”, „History and Theory”, vol. 19, no. 3/1980, p. 274. ↑

16. W. Włodarczyk, op. cit., p. 6. ↑

17. J. Topolski, “Jak się pisze i rozumie historię. Tajemnice narracji historycznej”, (Poznań 2008), pp. 289–290. ↑

18. This is how Michel Foucault desccribes the vision of history, see. J.J. Scheurich, K. Bell McKenzie, “Metodologie Foucaulta […]”, op. cit., p. 304. ↑

19. Ibidem, p. 6. ↑

20. Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis explain transference in psychoanalysis as “proces aktualizowania się nieświadomych pragnień wobec pewnych obiektów w pewnego typu relacjach z nimi, przede wszystkim w relacji analitycznej. Chodzi tu o przeżywanie dziecięcych wzorców, które przeżywane są tak, jakby działy się w rzeczywistości. […] Freud zauważał, że przeniesienia nie różnią się od siebie w zależności od tego, czy skierowane są na analityka czy na inną osobę; ponadto są one pomocne w leczeniu jedynie pod warunkiem, że są kolejno wyjaśniane i burzone. Przeniesienie jest zarazem formą oporu wobec leczenia, sygnalizując zarazem bliskość nieświadomego konfliktu”. See J. Laplanche, J.-B. Pontalis, “Przeniesienie”, in: “Słownik psychoanalizy”, transl. E. Modzelewska, E. Wojciechowska, (Warsaw 1996), pp. 260–261. Dominick LaCapra pointed to the important role of transference in constructing history, as well as in the ethical and political lives of societies, see D. LaCapra, “History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory”, (Ithaca–London 2003), while in reference to art and art history, the observation was made by Mignon Nixon, see M. Nixon, Oral Histories: Silvia Kolbowski and the “Dynamics of Transference”, in: “Silvia Kolbowski. Inadequate... Like... Power”, ed. R. Frank, cat., Secession, (Wien 2003), pp. 93–102. ↑

21. LaCapra, “History in Transit”, op. cit., p. 74. ↑

22. In context of the observations of Andrzej Kijowski, the category was later noted by Wojciech Włodarczyk, see “Nowoczesność i jej granice”, in: “Sztuka polska po 1945 roku”, op. cit., p. 21; A. Kijowski, “Pisarz i urząd”, in: idem, “Niedrukowane”, (Warsaw 1978), p. 6. ↑

23. R. Leys, “From guilt to shame. Auschwitz and after”, (Princeton–Oxford 2007), pp. 11–14. ↑

24. For rhetorical tropes in historical narrative see J. Topolski, “Jak się pisze i rozumie historię...”, op. cit. ↑

25. R. Leys, op. cit., pp. 132–152. ↑

26. D. Crimp, “Mario Montez”, For Shame, in: “Regarding Sedgwick: Essays on Queer Culture and Critical Theory”, ed. Stephen M. Barber and David L. Clark, (New York: Routledge, 2002), p. 65. ↑

27. Izabela Kowalczyk was the first one to have written about a strained art history in this context, see I. Kowalczyk, “Zwichnięta historia sztuki? – o pominięciach problematyki żydowskiej w badaniach sztuki polskiej po 1945 roku”,

http://historiasztuki.uni.wroc.pl/opposite/opposite_nr1/izabela_kowalczyk.htm [data dostępu 22.09.2011]. ↑