Primary Forms

III edition

Primary Forms is a periodic programme designed for pupils from the fourth through the eighth grade of primary school, carried out by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and the Roman Czernecki Educational Foundation. This year sees its second edition.

The program includes the creation of a box housing a proposal for an exhibition, which can materialize at any time in a shape chosen by the pupils, supported by the teachers' staff and the Museum's education team.

Among the artists who prepared their unusual artworks this year, especially at the invitation of " Primary Forms," were 8 artists from Poland and abroad: Adriano Costa, Jaroslaw Flicinski, Veronika Hapchenko, Edith Karlson, Krzysztof Maniak, Ahmet Öğüt, Olivia Plender, Laure Prouvost.

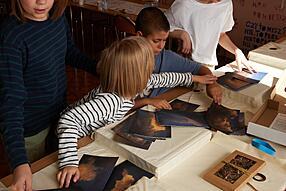

Their works were packaged in special toolboxes designed by architect Maciej Siuda (resembling large pencil cases in shape) and sent to 10 selected elementary schools from towns of less than 30,000 residents in the Mazovia Province and 4 cultural institutions.

The boxes and the artworks in them are the basis for further activities carried out in schools. They are "dormant" art, instructions and proposals for artistic activities and experiments, which are an invitation and inspiration for pupils to work together to prepare their own works of art and final exhibitions in the space of schools (in classrooms, corridors or on the playground). They will be assisted by their teachers and museum educators from the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, who will visit the schools.

Designed in the form of artistic exercises and objects placed in the box, the exhibition refers to the tradition of art history: to Marcel Duchamp and his travelling exhibition-in-a-suitcase, as well as to “Fluxkits” – boxes prepared by artists affiliated with the Fluxus movement, containing scores, models, audio recordings, games, puzzles, and stencils, among other items. Primary Forms also alludes to other experiments in the fields of art and education undertaken in the 20th and 21st centuries, such as Pure Consciousness – the series of On Kawara’s exhibition in kindergartens, initiated in 1998. Paintings by this Japanese conceptual artist could be used as teaching props helping to learn the days of the week and numbers.

The programme is carried out in classrooms and corridors, gym halls and schoolyards. The exhibition in a box can be executed numerous times and interpreted in various ways (through the selection of different fragments, scale, colours, etc.). We use it to ask the following questions: what can we do with art? What can an exhibition be? What can we learn from artists? Is knowledge created through contact with art? And finally, how to understand art or enjoy not understanding it?

Primary Forms was inspired by the School Prints initiative, carried out for a brief period in the UK right after World War II. On that occasion, a set of lithographs created by a group of esteemed artists was sent to primary schools. Those artists included Barbara Jones, Henri Matisse, Henry Moore, John Nash, and Pablo Picasso, among other figures.

The Primary Forms programme is developed under the curatorial supervision of Sebastian Cichocki and Helena Czernecka.

read more on the website:

formy.artmuseum.pl

Curatorial team: Sebastian Cichocki, Helena Czernecka

Box design: Maciej Siuda, współpraca: Adrianna Gruszka

Graphic design: Zofia Kofta

Production coordinator: Marta Wójcicka, Stowarzyszenie Artanimacje

Conception and coordination of educational process: Anna Grajewska, Anna Łukawska- Adamczyk, Marta Przybył

Substantive consultation: Aleksandra Saczuk, Urszula Arciszewska (Fundacja EFC)

Texts: Sebastian Cichocki, Helena Czernecka, Jakub Depczyński, Bogna Stefańska

Editing: Kinga Gałuszka

Translation: Joanna Figiel

Communication: Jakub Drzewiecki

Artists: Adriano Costa, Jarosław Fliciński, Veronika Hapchenko, Edith Karlson, Krzysztof Maniak, Ahmet Öğüt, Olivia Plender, Laure Prouvost

Educators: Wiktor Bebacz, Alicja Czyczel, Aleksandra Górecka, Magdalena Kreis, Aleksandra Kubisztal, Justyna Łada, Maria Nowak, Paulina Pankiewicz, Marta Przybył, Natalia Skipirzepa, Marta Węglińska, Karolina Zięba, Gabriela Żylińska

Teachers: Renata Andraka, Aneta Bielska, Monika Byszewska, Marzena Kudelska, Beata Kulka, Monika Metera, Bożena Nowak, Janusz Nowak, Maria Nowak, Joanna Pec-Pawlik, Iwona Pieńkos, Marta Wesołowska, Agnieszka Wójcicka, Ewa Żydek

Schools:

Szkoła Podstawowa im. gen. Józefa Dwernickiego w Rudzie Wolińskiej,

Zespół Szkolno-Przedszkolny w Młochowie,

Szkoła Podstawowa im. Wołyńskiej Brygady Kawalerii w Dębem Wielkim,

Publiczna Szkoła Podstawowa im. mjra Henryka Sucharskiego w Jelonkach,

Szkoła Podstawowa z Oddziałami Integracyjnymi w Dzierżeninie,

Szkoła Podstawowa im. prof. Jadwigi Kobendzy w Koczargach Starych,

Zespół Szkolno-Przedszkolny im. Kornela Makuszyńskiego w Wyszynie,

Szkoła Podstawowa im. Władysława Stanisława Reymonta w Maszewie Dużym

Publiczna Szkoła Podstawowa nr 2 w Garwolinie,

Publiczna Szkoła Podstawowa im. Kornela Makuszyńskiego w Chynowie,

Institutions:

Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych w Ostrowcu Świętokrzyskim,

Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych w Tarnowie,

Galeria Bielska BWA,

Gminne Centrum Kultury w Okuniewie.

Adriano Costa

Adriano Costa is a Brazilian artist and sculptor. Since birth, he has lived in the largest city in South America, São Paulo, and the city remains one of his most important inspirations. In his work, he attaches great importance to materials and sees them as carriers of personal stories, memories, and values – symbols representing economic and social transformations of the city.

Costa carefully juxtaposes different kinds of objects – from used fabrics, through objects found on the streets of São Paulo, to custom-made bronze castings, wooden elements or concrete blocks. They serve as elements of eloquently-titled installations that often link his mysterious and complex compositions with specific events in Brazil’s history and sometimes provide a little light relief.

Costa is a versatile and inventive creator. Thanks to how he juxtaposes, repaints, and arranges the seemingly familiar, often worn-out objects, they gain a new life. As the artist admits, it is not important whether he works with plastic rubbish found on the street or precious metals – he sees all objects as equally important and valuable, both as artistic forms and tools for conveying ideas, memories, and emotions.

Jarosław Fliciński

According to the artist, his “paintings slipped off the canvas onto the walls.” And he continues: “This was at the point when the frames became simply too small or my work did not fit the exhibition space because of its scale, colour, or light.” Fliciński is known for large-format, abstract works, in which he employs geometric forms, repetitive patterns, and rhythmic lines. He paints in series that feature recurring motifs, often inspired by elements of the surrounding reality – e.g. the pattern of tiles in a swimming pool or mass-produced wallpaper. They also reflect the warmth and colours of the Portuguese coast, where the artist spent a large portion of his life.

Fliciński's compositions escape the notion of what was traditionally understood as painting. First, they “moved beyond” the frame and turned into murals, and later transformed into multi-element installations in various spaces outside the museum and gallery. Although Fliciński also uses photography, video and sound, painting and geometry – which he considers the best tools for conveying emotions – always remain at the heart of his artistic endeavours.

Veronika Hapchenko

As a child, Veronika Hapchenko and her parents came to Poland from Kyiv, Ukraine. She spent most of her later life in Kraków, where she studied painting at the local Academy of Fine Arts. She also completed stage design studies at the Kyiv National University of Theatre, Cinema, and Television. There, she designed puppet theatre scenography – she was fascinated by the way in which inanimate objects could be brought to life. There was something magical about it.

Veronika’s paintings appear bleary and pulsating. This is because of her particular technique, involving the use of an airbrush – a gun-like device that sprays paint with an air jet. Beyond the blurred surface, there are also figures, elements of buildings, and objects that refer to the history of the former republics of Soviet Union. Narratives from that era often feature magicians, shamans, mystics, healers, and visionaries appearing in a seemingly ordered, controlled and predictable world. The artist seeks them out and translates them into her painting. She is interested in, for example, Russian cosmism, a movement that emerged at the turn of the 20th century that explored the relationship between man and the universe.

From these hazy stories, esoteric tales, and secret symbols, the artist picks out the characters and objects that populate her paintings. Hapchenko's work is therefore an invitation to other universes – the world of spiritualism and magic hidden beyond a reasonable, intellectual and artistic facade. She believes in the power of intuition: “I do not know why the painting looks this, and not another, way. These are simply impulses which I’d prefer not to explain,” she says.

Edith Karlson

Edith Karlson is an Estonian artist who lives and works in Tallinn. She teaches at the Estonian Academy of Art, where she studied at the Faculty of Sculpture and Installation. In her works, the artist employs a variety of sculptural techniques – from traditional ceramics to large-format cement structures. The artist’s works are typically large scale; instead of focusing on minute details of individual sculptures, she juxtaposes them into complex installations and spatial arrangements.

Karlson’s protagonists are most frequently animals – each of her installations is a separate world inhabited by snakes, dogs, cats, birds, rabbits, and dinosaurs. Sometimes they are also accompanied by beasts and imaginary creatures, as well as human figures resembling phantoms. Although seemingly friendly and charming at first glance, her works are underpinned with a sense of anxiety and horror. An encounter with a group of ceramic animals and creatures staring straight back at the viewer can resemble reading fairy tales, myths, and legends – something seemingly innocent becomes a vehicle allowing us to commune with the world of darkness which we choose not to confront on a daily basis.

Ahmet Öğüt

Born in Turkey, Ahmet Öğüt is an artists of Kurdish origin who currently lives and works in Amsterdam and Berlin. He describes his art as, primarily, the starting point of processes that can lead to unpredictable results. Ahmet’s works, created in collaboration with people unrelated to the art world (a stuntman, hairdresser, or firefighter), are usually light in form and draw from local history and memory of a given place. The artist is not attached to a single medium – depending on circumstances, he uses photography, video, drawing or performance, but has also used a boat, trampoline, giant balloon, or barricades made of paintings or stilts. He is famous for his sense of humour, which allows him to tackle difficult issues such as refugee and migration policy, war, or racism.

A large part of Ahmet’s activity is dedicated to education. He works as a lecturer at several universities, including in Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, and Austria. He is also one of the founders of The Silent University (established in 2012) where lectures are delivered by displaced people and forced migrants. Ahmet believes that there is no need to learn art – we can and should learn many other things, while art is something that we should just make.

Krzysztof Maniak

Krzysztof Maniak's studio is the landscape and the artist’s relationships with it – he traverses, digs up, plants, and moves its elements. Walking is part of his artistic work – he writes down specific instructions or “walking scores” which he then uses on his jaunts. “For several years, I have been creating a series called Walks. In it, I explore the sculptural potential hidden in the workings of natural forces or non-human beings – rotting trees and hay, landslides, mysterious holes and ditches in the ground” – says Maniak.

Walks also inspire him to create works for other species – sculptural hay racks or trenches in which animals can live or transform for their own use, digging holes and burrows in them.

The artist draws from what is closest to him, at hand. He is closely linked to Tuchów, his hometown in southern Poland: “Even though […] the entire town occupies an area of just 22 sq km (or 8.5 sq miles), I can find everything here. I know this landscape like the back of my hand, and crucially, I can see all of it at once, which gives me the impression of security and homeliness,” — he says.

Maniak is directly inspired by 1960s and 1970s conceptual and land art, but the spectre of the current climate emergency is equally important to him. He says that it is the source of his sensitivity and paying attention to even the smallest element of the larger whole – such as the shells of burgundy snails, blackthorns twigs or the trunk of an eighty-year-old tree, buried in the ground in a mourning ritual.

Olivia Plender

In her work, the British artist, Olivia Plender mainly focuses on the history of education. She says: “I am interested in the two contradicting ideas: education as training in the workplace and education as an emancipatory practice.” Plender’s art is based on historical materials, literature and archival research, from which she extracts interesting facts about unusual pedagogical methods and social organizations in the 19th and 20th centuries. Based on this data, she creates installations, films and comics, and organizes meetings and discussions with contemporary activists working towards a just and compassionate world.

Plender is most fascinated by examples of experimental education. The artist emphasizes the importance of play, referencing examples from her native London and the surrounding area. She is interested in, for example, the history of the youth organization, The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, active in early 20th century, which combined a passion for crafts, climbing, camping, and helping those in need.

The artist’s favourite medium is drawing: “[…] it's a cheap and fast medium – all you require is a pencil and a piece of paper. When I graduated from art school, I wanted to make films, but I had neither studio nor money, so I drew comics instead,” she says.

Laure Prouvost

French artist Laure Prouvost is known for mesmerizing installations consisting of elements such as films, sounds, performance, sculpture, fabrics, and texts. Experiencing her works is often accompanied by feelings of uncanniness and uncertainty whether what we are experiencing is real or imaginary. Prouvost creates new worlds by referencing the traditions of Dadaism and Surrealism and juxtaposing elements that are seemingly incompatible with each other.

She frequently returns to the idea of escaping towards a parallel reality. While moving away from traditional methods of building a narrative, she creates captivating landscapes, full of extravagant characters, songs, and word play. In her work, language is disobedient and imprecise, and objects exceed the limits of their own abilities, come alive, speak or even joke.

The flexibility of words is a key element of Prouvost’s art: “To me, words are visually powerful because through them, we can create our own visions. I only make suggestions and suggest possibilities, and the viewers create their own images. I also focus on the meaning of misunderstanding, misinterpretation, and miscommunication – words can also be a failure, highlighting the importance of other senses,”she says.

Maciej Siuda

Maciej Siuda is an architect who designs houses and exhibitions, but also works on smaller, art-related projects, such as the “toolbox” that houses this year’s “Primary Forms.” As he says, he often thinks of architecture as a collection of verbs (for example: to do, make, use, change, domesticate, etc.), rather than nouns (for example: material, wall, building, etc.).

Siuda always begins with small drawings and models, and later experiments with different solutions at various scales. He has worked in many places around the world, including the Sou Fujimoto design office in Tokyo, and designed buildings and art installations in Spain, Italy, Indonesia, Poland, Kenya. In Haiti, his design for a primary school in Jacmel now stands on a site demolished by an earthquake. In Warsaw, Poland, he designed a school building that consists of seven cube-shaped blocks in colours inspired by the nearby Kabaty Forest.

The architect frequently collaborates with visual artists. For example, the staircase and façade of the school in Warsaw are decorated with a red railing designed by sculptor Monika Sosnowska.